Preface

It is painful to follow the news from Iraq these days. Five years of war and violence have destroyed the nation, taken tens of thousands of lives, left its cities in ruins, littered the countryside with the debris of battle, caused untold environmental damage and shredded the fabric of political and civil society. Few Americans remember, if they ever knew, that Iraq was once one of the most advanced nations of the Middle East, with a prosperous economy, high standard of education and health care, and a vibrant cultural life. Twenty-five years of dictatorship under Saddam Hussein brought an end to any political progress that Iraq had made, but this war, initiated by the United States, has completed the economic and cultural devastation of the nation and sent many of its best educated and most qualified leaders into exile. It is hard to see how the nation can ever be restored. This was not part of the dream of the founders ninety years ago.

The nation of Iraq was created by Great Britain in the aftermath of World War I out of three provinces of the defeated Ottoman Empire. In 1920 the League of Nations recognized it as a new state and awarded a Mandate to Britain to guide and prepare it for independence and self government. Though it seems clear that they expected to maintain control of the area indefinitely, the British moved quickly to establish an Iraqi government through which they could continue to exert their influence, and to give legitimacy to this effort, they sought to appoint an Arab king. And so on August 23, 1921, the Emir Faisal of the Hejaz, son of the Sherif of Mecca, was crowned King of Iraq, and the nation began its journey toward independence.

Just one year later my father arrived in the southern Iraqi city of Basrah to begin a three year assignment as a teacher with the Arabian Mission of the Reformed Church in America. His appointment was to the School of High Hope, the Mission school for boys, which had been established ten years earlier. His responsibilities were to teach English, oversee the sports and extracurricular programs, and supervise the small boarding department. During vacation times he had an opportunity to visit other places in Iraq as well as neighboring countries. It was an interesting time to be in Iraq, a country in transition from imperialism to independence, a land of hope and expectation, a place so different from the Iraq we have come to know in recent years.

Every week for almost three years, Dad faithfully wrote to his parents and siblings back home in Pella, Iowa and set the pattern which his two brothers and sister also followed when they left home, and which all continued for the rest of their lives. The “Dear Ones Everywhere” letters were a weekly obligation, and they chided each other when any one of them missed a week or even sent off the letter a day or two late. When Dad died unexpectedly in 1990, my sister found the weekly letter, with its five carbon copies - for his three siblings and three children - already half written in the typewriter. Though we may have secretly admired this habit, we cousins joked about the letters. There was a stock formula: a brief weather report, comments on family news from letters received that week, then a report of the weeks activities, and perhaps a commentary on the state of the world or some particular issue that, in Dad’s words, “got my goat” that week. That, too, was the pattern of Dad’s early letters from Basrah.

Our grandparents kept the Basrah letters, which were returned to Dad after they died. We discovered them again only after his death, when we were helping Mother close up their house in Tucson, Arizona, where they had lived in retirement. When I first saw the letters, I was excited because I hoped they would shed light on that period of Dad’s life and also on the early history of Iraq , but when I read them I was disappointed. The letters did reveal a great deal about the young George Gosselink, but on first reading seemed to say very little about what was happening in Iraq and the Middle East.

It is not that Dad was unobservant. He also kept a travel diary, and his entries, when he was away from Basrah, often contain lengthy descriptions of the people and places he visited that do not appear in the letters. Even then, when his ship stopped at Port Said on his way out to Basrah, when for the first time he came into contact with Arabs and their culture, he wrote only that he had had his “first smell of the East, tho there wasn’t very much to see.” Shortly after he arrived in Basrah he reported that he had gone out to see the town and visit the school, but he offered no description of the people, the streets and the buildings, all of which would have been completely different from anything he had known in Pella. As a young man just arrived from Iowa, he may be forgiven for not knowing much about the political situation in Iraq , but when he did write about what was happening, he seemed to share his mentor John Van Ess’s views rather than his own observations. He rarely said anything about what was happening in the country, the political developments in Baghdad or the continuing unrest in other areas. He wrote of spending time with his students and visiting them in their homes, but he seldom reported what they talked about, what their interests were, and what they thought, for example, of the continued British presence in their midst. And he almost never gave the names of his students, fellow teachers and other friends.

But then, he did not see himself as a reporter but only a dutiful son keeping in touch. When he first arrived he may have been so overwhelmed that he did not know what to write. And after some time, when the novelty wore off, he did not think to provide the details which would be so interesting to us now.

In part he may have been sparing his parents the facts which he felt they would not understand. Sometimes he was shielding them from the news which might have caused them anxiety. His letters describe his own activities during the week, the routine of the school, the comings and goings of other missionaries and travelers, and the occasional special outings. And after he had been there a year, there was a lot of repetition, as the calendar determined the weather, the school schedule, the local holidays and festivals. I found the letters somewhat banal, and set them aside.

In the months leading up to the start of the war in 2003, I was often asked to speak on Iraq. Since I had been born in Basrah and lived there until I was eighteen and had visited several times after that, I was thought to have some knowledge of the area. In preparing those presentations, I took a renewed interest in the history of that country and my parents’ experience of living there for almost forty years. Iraq , as late as 1960, was a very different country from the one we hear about today. And when I thought of my father’s letters again, I realized that the very ordinariness of his life in Basrah in the 1920s is significant and gives a picture of Iraq and the Iraqi people that is simply not seen today. The people of Basrah had electricity and potable water, their police could apprehend thieves and restore stolen goods, the courts functioned to resolve disputes, shops carried a wide inventory of goods, followers of different faiths lived together in seeming harmony. I would not put too rosy a tint to this picture - the poor did not enjoy all these benefits and religious prejudice was not far below the surface - but there was a fair degree of security in the ordinariness of life, and there was the expectation that conditions would improve. Dad’s letters reflect that reality, and so I decided, on further thought, that there would be some benefit in transcribing and sharing them.

His letters are long and rambling and, as I have mentioned, often include a weather report, his response to news of family and friends, and long commentaries which are not very relevant today. Taking inspiration from Florence Bell, who edited the letters of her stepdaughter Gertrude Bell (note 1), written from Iraq 1917-1926, I have selected and edited Dad’s letters, cutting out a great deal but including those things which shed light on the nation of Iraq and its people, the lives and work of the missionaries, and his own activities and experiences. That done, I have been surprised and pleased to discover how interesting and informative they are.

While I have edited his writing and spelling, I have tried to retain his style and idiosyncrasies. Sometimes his language and opinions seem to be politically insensitive by the standards of our time, but they represent the usage and attitudes of his time. For example, his use of the word native (as in “The natives are celebrating their new year.” or “I have learned to like native food.”) jars our ears, but it was the common idiom then. He uses Mohammedan where we might prefer Muslim. He was interested in Arab customs and ways of doing things but was not always sensitive to cultural differences and was quick to make judgments. He observed once that the Arabs have no family life, though he visited their homes, shared in their special feasts, and commented once on the attitude of respect that sons showed their fathers. What he meant was that they did not gather together as his family would at home. Women did not socialize with men and were not seen at these feasts, though their role in the family was very important and influential. He could not observe that side of Arab family life.

On a number of occasions Dad expressed regret that he did not speak Arabic. He knew that he would have had a much better understanding of the culture if he had been able to converse with his students, hosts and other friends in their own language. Career appointees to the Arabian Mission were required to spend at least two years in language study before they were given their first assignments. As a “short termer” Dad plunged right into work without any preparation. He did pick up a little Arabic from his students and seems to have been able to communicate with even the youngest of them in some mixture of Arabic and English. He was very popular with the boys, who knew him as “Mister George” - the name he carried for the rest of his career in Basrah.

Understandably, Dad wrote about the unusual or special events in his life rather than the routine. He lived at the school and took all his meals with the boys in the boarding department, but he wrote about visits to his students’ homes and especially about the holiday feasts at the Van Ess house and moonlight picnics on the river. He liked his Mission colleagues and they seem to have been fond of him. John Van Ess and Dirk Dykstra appreciated the fact that he spoke Dutch. I have been especially taken by his references to members of the mission “family,” those same uncles and aunts that I knew as a child, and his description of holiday feasts and moonlight picnics are identical to what I remember of twenty and thirty years later.

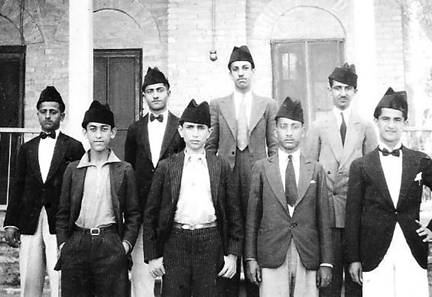

Dad was there to witness the very first years of Iraq’s nationhood. He expressed some skepticism of “Arab government” and felt that most Basrawis would have preferred British rule. But he also saw a change taking place. Some of his students wanted to go abroad, especially to the United States , for further education but they all expected to return to serve their country. They were beginning to think of themselves as Iraqis. When Dad first arrived in Basrah in 1922, most of his students were still wearing the Turkish fez. When he returned in 1929, they were wearing the sidara, the unique Iraqi hat that had been introduced by King Faisal. It was a small symbol, perhaps, but a sign of the hope that characterized the new Iraq at that time in its history.

September 15, 2008CGG

Basrah Boys School Students, 1932

References:

[1]The Letters of Gertrude Bell, selected and edited by Lady Florence Bell, 1927.